China’s highest planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), announced on January 5 that it is looking at further measures to reduce plastic waste pollution.

It has promised rules on plastic products that are comprehensive and detailed, as well as more bans, and an accelerated switch to less polluting materials.

There is a useful precedent in China’s 2008 restrictions on ultra-thin plastic bags, which started an effective clean-up of a once-universal form of litter. The NDRC’s new moves are expected to revise the March 2008 order, which banned bags thinner than 0.025 millimetres, and compelled retailers to charge for plastic bags.

The new measures are likely to focus on the highly visible waste packaging generated by the rise of online retail and popularity of takeaway food. These both depend on courier delivery services that have expanded the amount of plastic packaging in use since 2008, according to Wang Tao, who heads Tsinghua University’s Solid Waste Control and Utilisation Institute.

Data from the State Post Bureau shows that 31.28 billion items were sent express delivery in China in 2016, using 3.2 billion postal bags, 6.8 billion plastic bags and 330 million rolls of packing tape.

Online delivery services also generate vast quantities of plastic waste. A China Youth Daily report claims that about 20 million orders are made each day from three major online services, producing more than 60 million plastic cartons based on a typical order of three dishes or more.

Ocean of waste

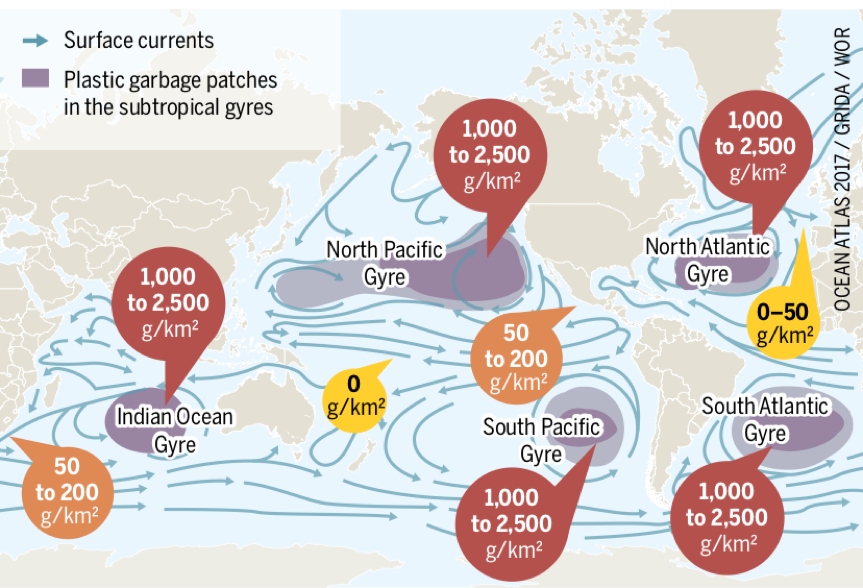

Globally 80% of plastic litter found in the ocean originates on land, with shipping accounting for the rest, according to the most recent Ocean Atlas published by Germany’s Heinrich Böll Foundation.

While measures in China to limit waste packaging are welcome and should help to reduce ocean pollution, analysts say seaborne plastics are already causing serious damage to marine ecosystems and require specific targeting and more monitoring – something that is in its earliest stages.

Monitoring work in 45 ocean areas found that 84% of floating waste and 68% of waste on beaches was plastic, according to the 2016 China Marine Environmental Status Bulletin, published by the State Oceanic Administration.

Monitoring of beaches in 12 Chinese coastal cities, including Shanghai and Shenzhen found that four of the five commonest types of litter were plastic – and plastic bags are the most frequent. Twelve non-governmental organisations carried out the monitoring, including Shanghai Rendu Ocean Centre.

Both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans now have patches of floating garbage larger than some countries – for instance a patch bigger than Mexico in waters off Peru and Chile. These plastic patches are difficult to spot because they are not solid islands of garbage but water that is soupy with microplastics.

Areas of the ocean where plastic has accumulated. Source: Ocean Atlas 2017

Difficult decisions

“Deciding which products should be restricted, and to what extent, is a challenge facing both China and the rest of the world,” says Yu Weidong, head of the Oceans and Climate Centre at the State Oceanic Administration’s First Oceans Institute.

He says a total ban is impossible, as it would mean giving up the tools of modern life such as cars, planes, computers and mobile phones.

German chemical giant BASF has developed biodegradable plastics that it calls ecovio and ecoflex. However, while they offer the benefit of being compostable, they are not a complete solution because they break down slowly in seawater, BASF press officer Tian Lijun told chinadialogue.

A technological fix to the problem of marine plastic waste is not the solution, added Tian: “Litter in the oceans is mainly caused by failings of human behaviour and waste management. The keys to resolving the problem are good waste management infrastructure and consumer education.”

First steps

Given that China is already working to tackle air and water pollution, there is limited capacity in government to address the problem of marine plastic waste too, says Li Daoji, a marine environment expert and professor at the State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research at East China Normal University.

Furthermore, there has been little international progress on dealing with marine plastics, with no strong global negotiation and governance mechanisms in place.

The UN Environment Assembly passed a draft resolution on marine litter and microplastics in December 2017, setting only a soft, non-binding target to “prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds” by 2025.

China attended the assembly, but has not yet signed up to the UN Environment Programme’s #CleanSeas campaign.

It calls on governments, businesses and individuals to take measures to stop plastic litter reaching the seas. So far 39 countries have joined.

“China’s signing up would be of huge benefit to the cleaning up of ocean litter,” said Sam Barratt, chief of public advocacy and communications with UN Environment, adding that membership is not mandatory – countries decide whether and when to participate based on their own circumstances.

Measuring the problem

China was identified as the world’s largest source of marine plastics in research published in the journal of the International Solid Waste Association in February 2015

However, as the researchers explained, the estimate was quite rough because it was based on “linking worldwide data on solid waste, population density, and economic status”.

More data is needed.

“There’s an urgent need for a single international standard for quantifying, monitoring and assessing plastic and microplastic litter, so that the findings of different pieces of research can be compared,” says Yu.

Li says that a number of influential models of marine plastic litter quantities have been released since 2015 but they are based on estimates not actual measurements so the conclusions would need to be confirmed through long-term monitoring.

The term microplastics refers to tiny fragments of plastic created when larger plastic litter breaks down in the ocean, and also the plastic microbeads added to some cosmetic products.

Monitoring of 12 Chinese beaches found that four of the five commonest types of litter were plastic (Image: structuresxx/ Thinkstock)

China’s initiatives

Li’s team is working on developing technology to monitor marine microplastic pollution, supported by 16 million yuan (US$2.5 million) from China’s Ministry of Science and Technology.

The project started in 2016 and aims to monitor microplastics entering the sea from China’s major rivers, such as the Yangtze and Pearl River. This will determine the scale of the problem, including China’s contribution to the global problem.

The National Marine Environment Monitoring Centre collected the first data on density of microplastics in China’s coastal waters in 2016. It found one piece of microplastic in every 3.5 cubic metres of seawater in the Bohai Sea, the East China Sea and the South China Sea.

This is a relatively low figure in global terms, Wang Juying, deputy head of the monitoring centre, part of the State Oceanic Administration, told a marine environment conference in August 2017. Similar density levels are found in the Southern Ocean and Japan’s Seto Inland Sea.

But she pointed out that China has been producing plastic litter for a shorter period than developed nations, and so the issue still needs attention.

Microplastics smaller than 150 micrometres in size can end up in the circulatory and lymphatic systems of marine life, and then make their way through the food chain to the human body. “Scientists regard microplastics as the ‘PM2.5 of the sea’”, said Wang, referring to tiny particles of air pollution that damage human tissue.

Wang pointed out that more and more people are saying pollution from microplastics of less than five millimetres in diameter cannot be ignored and may constitute a marine crisis on a par with climate change and ocean acidification.

The NDRC has requested expert comment to shape its as-yet unpublished measures.