Editor’s Note: This article forms part of a Special Report on economic decline and rejuvenation in China’s former coal belt. In part two photographer Stam Lee explores Fuxin, a hollowed out pit town pinning its hopes on wind power in photo essay, accompanies by a report co-authored with China Dialogue reporter Feng Hao.

Once the heart of China’s heavy industry, the country’s north-east is in trouble; its oil fields and steel mills are struggling, and its coal mining sector is in chronic decline.

The consequences of decades of rapid economic development started to attract attention in the early years of the century. Between 2008 and 2010 the government identified 69 “resource depleted cities” of which 19 – more than a quarter – are in the north-eastern provinces of Jilin, Liaoning and Heilongjiang.

Most of these 19 cities primarily mined coal but with the sector in decline, an urgent search is on for new economic opportunities. Many of the problems faced by China’s north-east reflect the broader need for China to shift to more sustainable economic development as environmental pressures force it to restore the environment and reduce carbon emissions.

Resource depletion

It is getting harder to mine coal in the north-east. Most seams have been mined too extensively, with some pits descending over a kilometre down into the earth.

At those depths, the temperature and humidity become problematic for large machinery so more labour intensive methods are used. But the higher labour costs mean that the cost of coal mining has rocketed to unsustainable levels.

According to a recent report, jointly published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Institute of Urban and Environmental Studies and the Research Institute for Global Value Chains at the University of International Business and Economics, coal companies nationwide employ on average 11 people per 10,000 tonnes of coal output. However, industry leaders such as Shenhua and the China National Coal Group have reduced this to 4-5 people. In contrast, older north-east companies such as the Jilin Coal Group and Shenyang Coal Group employ around 21, and the Heilongjiang Coal Group employs 48 – four times the national average.

The additional labour increases costs. The Heilongjiang Coal Group pays 451 yuan to extract one tonne of coal, with labour costs accounting for 215 yuan. This compares to less than 200 yuan for one tonne of coal for Shenhua.

The government has also put pressure on the coal sector in the north-east through policies to reduce coal power generation and steel output, aimed at improving air quality. In 2016, China saw its third consecutive year of reduced coal consumption, leading many to believe that the country’s coal consumption had already peaked. In 2016, the industry was instructed to reduce coal output by about 500 million tonnes over the next three to five years from a current level of 3.8 billion tonnes per year.

New jobs needed

The report estimates that by 2020 the coal sector will employ less than three million people, down from 5.29 million in 2013. This means that within seven years approximately 2.3 million miners will require reemployment.

Even during coal’s golden decade between 2004 and 2013, efficiency improvements reduced the need for labour. Between 2000 and 2012 the average number of employees per 10,000 tonnes of coal produced more than halved, from 29 to 14. Even without resource depletion and reductions in output, coal jobs in the north-east would have gradually been lost.

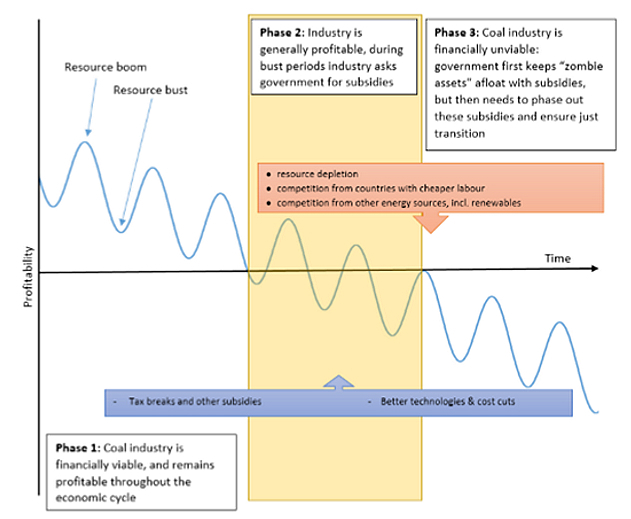

The falling profitability of coal mining firms

Source: International Institute for Sustainable Development

Looking for work

Former miners are finding it harder to find new jobs. Jiang Zhimin, deputy head of the China Coal Industry Association, said at the start of this year that in 2016 posts had been found for some by letting temporary workers go and moving others to new work. But as reduction in output continues, the coal industry is less able to find an alternative to making miners redundant.

With half of all miners over 45 years old and six out of ten educated to junior middle school level or less, finding new work is particularly challenging.

China’s large state-owned enterprises (SOE) are regarded as an extension of government, and a major SOE may have its own hospitals, schools, retirement homes and post office – it is a major part of life not just of its employees but for their children, too. The large state-owned coal mines of the north-east are a classic example of this.

“Only SOE or government jobs are regarded as real work,” says Wang Ran, an assistant researcher with the Research Institute for Global Value Chains. She has found that some miners prefer to stay in mines facing imminent closure, earning 800 yuan a month, rather than find more lucrative work elsewhere.

Some miners, despite being forced to look for new jobs, keep their shovels and other mining implements at home, in the hope that one day they can return to mining. Wang Ran explained that the hope the industry will one day recover keeps many from quitting the sector altogether.

No way back

According to a report from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) there are countless global examples showing how reduced employment due to macro-level industrial policies can have profound social impacts – especially in subsidised industries. The dilemma for government to deal with the coal mining cities is that if changes are not made then the financial costs and environmental risks can be enormous, but if changes are rapid and drastic, a range of social problems may arise.

And once a transition is underway, it cannot be reversed. In this, China’s policy makers appear to have accepted that a transition is inevitable, unlike in the US where the Trump administration is looking to revive the flagging coal sector.

There appears to be little hope for a revival of the coal industry, which must contest with China’s changing economic structure, the rise of service industries, and the development of new energy sources, says Huo Jingdong, deputy head of the Beijing Municipal Institute for Economic and Social Development.

A hard road ahead

In the short term, SOEs can be subsidised while they operate at a loss and reduce costs by cutting working hours and salaries, says Richard Bridle, senior policy advisor at IISD. But such fixes are not long term solutions.

Cutting workers is the only option, argues Bridle, but it must go hand in hand with an effort to create new employment opportunities elsewhere so that miners can be reemployed. Fuxin, a coal city in Liaoning, is developing wind power generation and manufacturing. In 2016, the city had 1.89 gigawatts of installed wind power, accounting for 30% of the province’s total wind power generation. Fuxin now gets half of its power from the wind.

Commenting on this, Zhang Ying, an assistant researcher with the Institute of Urban and Environmental Studies, said that such efforts to replace jobs in mining cities are just getting underway and there are significant uncertainties over future funding and market prospects. Also, most of the replacement industries are in technology or capital intensive sectors so won’t provide as many jobs as the labour intensive coal sector. There are also technical obstacles to the reemployment of miners.

There appear to be few good case studies to emulate internationally. The IISD notes in its report that Asturias in Spain offered early retirement to miners facing similar issues. This resolved short and medium term issues but meant there was little impetus for long term development.

There is one ray of hope though for the north-east’s mining cities in the form of regional transport projects. Liu Qiang, head of the Energy Research Office at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Institute of Quantitative and Technical Economics, says efforts to prop up failing cities should in some cases be abandoned in favour of developing city clusters around major regional cities such as Harbin, Changchun, Shenyang and Dalian. The good rail networks can be further developed, along with other types of communications infrastructure. He suggests that cities within a half-hour train journey should “huddle together for warmth.”